I’ve been teaching biochemistry for more than two decades, and while the progress in the field over this period has been extraordinary, I continue to be astounded by what scientists were able to accomplish with the limited tools available to them in the era before molecular genetics and genomics. Recently while searching for ideas* for a writing assignment related to protein function, I was inspired to read Linus Pauling and coworkers’ groundbreaking 1949 Science paper reporting on their study of the molecular basis of sickle cell disease (SCD). While the molecular and genetic basis of SCD are now well-established—to the extent that they are literal textbook examples—I was unfamiliar with the historic origins of Pauling’s discovery, and I felt an almost-fanatic appreciation while reading it.

I was, however, a bit taken aback when, in the very first paragraph, I came across the term “American Negroes” being used to describe a population in which SCD was particularly prevalent. Almost immediately, I began to contemplate why I should have such a feeling. After all, the term was in common use at the time.

I realized that only in the last several years have I become introspective about my own biases and prejudices, beginning to question even the idea of race. And if I planned to assign this paper as required reading for my students, I felt a need to say something about the subject. So I spent a Sunday afternoon composing the brief statement that follows, and I included it in the description of the assignment and writing prompt. Here it is, exactly as I presented it to my students.

A note about race and racism in science from Dr. Garoutte

Race is a social construct that has no biological basis. You will surely notice that the 1949 paper makes use of terminology regarding race that seems outdated or perhaps even offensive to readers over 70 years later. As the National Museum of African American History and Culture states (4):

The term “race,” used infrequently before the 1500s, was used to identify groups of people with a kinship or group connection. The modern-day use of the term “race” is a human invention.

And on another page, the NMAAHC also recognizes that although “race does not biologically exist, yet how we identify with race is so powerful, it influences our experiences and shapes our lives. (1) “One of those ways is how our society chooses to refer to groups of individuals who identify or are identified as belonging to a particular race. Furthermore, as Tom Smith stated in 1992:

Labels play an important role in defining groups and individuals who belong to the groups. This has been especially true for racial and ethnic groups in general and for Blacks in particular. Over the past century the standard term for Blacks has shifted from “Colored” to “Negro” to “Black” and now perhaps to “African American. (6)

The US has conducted a census every 10 years since 1790. The census in year 1900 was the fist to use the term “negro,” but only in the instructions for census takers. The Pew Research Institute notes, “In 1900, there were no specified categories on the census listing form, but the instructions called for enumerators to list “W” for white, “B” for “black (or negro or negro descent)…” and so on. (3)

According to USAFacts, “Negro” was added as a category in 1940. They further note (8):

For free people, the 1850 edition offered three “color” options on the census for free people: “White, black, or mulatto.” Census instructions provided no guidance on how Native Americans living under US jurisdiction would be counted. “Mulatto”, meaning someone of mixed white and Black ancestry, would be on the census through 1920…. The 1900 census was… the first to count all Native Americans, both on reservations and in the general population…. [In 1940,] Black Americans were coded as “Negro,” the first time that term was used as a racial category in the census. Censuses used the term… until 2010, sometimes combined with the terms “Black” and “African American.” The 2020 census offered Black and white Americans the opportunity to write in their ethnic origins for the first time.

Even the famed author and civil rights activist W.E.B. Du Bois wrote a letter in 1928 in which he used the tern “Negro” to refer to himself and others. He wrote (7):

“English,” “French,” “German,” “White,” “Jew,” Nordic” nor “Anglo-Saxon”… were all at first nicknames, misnomers, accidents, grown eventually to conventional habits and achieving accuracy because, and simply because, wide and continued usage rendered them accurate. In this sense, “Negro” is quite as accurate….

The term continued to be used on the US census for decades. The 2020 census was the first since 1940 to not include “Negro” as a category (8).

Science is not immune to racism, and indeed, has been (and continues to be) used to defend and sometimes even create the very idea of race. Our current understanding of race evolved in western Europe, along with the invention of modern western science and the Age of Reason. The Science History Institute’s Distillations podcast released a ten-part series in 2023 entitled Innate: How Science Invented the Myth of Race (5). Here is just one quote, from the first episode:

As Europeans colonized the globe, they encountered countless new things and became obsessed with categorizing them. They even made a whole new field of science taxonomy. And the father of taxonomy, the guy responsible for how we see the whole natural world—that was a Swedish botanist and doctor named Carl Linnaeus. He published his catalog of living things, Systema Naturae in 1735. In the tenth edition, he broke down Homo sapiens into four categories: Americanus, Asiatic, Afer, and Europaeus. And he color coded them red, yellow, black, and white.

I cannot recommend this podcast series enough.

Works Cited:

- Being antiracist. (2021, December 16). https://nmaahc.si.edu/learn/talking-about-race/topics/being-antiracist

- Changing racial labels: From “colored” to “negro” to “black” to … (n.d.). https://www.jstor.org/stable/2749204

- Cohn, D. (2010, January 21). Race and the census: The “negro” controversy. Pew Research Center’s Social & Demographic Trends Project. https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2010/01/21/race-and-the-census-the-negro-controversy/

- Historical Foundations of Race. National Museum of African American History and Culture. (2021, December 16). https://nmaahc.si.edu/learn/talking-about-race/topics/historical-foundations-race

- Innate: How science invented the myth of Race. Science History Institute. (2023, June 12). https://sciencehistory.org/about/projects-initiatives/innate/

- Smith, T. W. (1992). Changing Racial Labels: From “Colored” to “Negro” to “Black” to “African American.” The Public Opinion Quarterly, 56(4), 496–514. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2749204

- The name “negro.” Teaching American History. (2021, September 10). https://teachingamericanhistory.org/document/the-name-negro/

- USAFacts. (2021, May 26). How the census collected race and ethnicity data from 1790 to 2020. https://usafacts.org/articles/how-the-census-collected-race-and-ethnicity-data-from-1790-to-2020/

* I am indebted to UCLA Professor Emeritus of Biochemistry Albert Courey. Although I have never communicated with him, I found his assignment online and modeled my own after it.

Cranberry juice: I bought only unsweetened cranberry juice at Aldi in glass containers. Diluted 1:1 with water and sweetened with homemade simple syrup or Splenda, this is just as good and about as cost effective as Ocean Spray.

Cranberry juice: I bought only unsweetened cranberry juice at Aldi in glass containers. Diluted 1:1 with water and sweetened with homemade simple syrup or Splenda, this is just as good and about as cost effective as Ocean Spray. Orange juice: Switched back to using

Orange juice: Switched back to using  Grapefruit juice: I cannot find this in concentrated form, but Food 4 Less carries Florida’s Natural brand in a 52-ounce waxed paper carton. (Walmart stopped carrying this in 2020).

Grapefruit juice: I cannot find this in concentrated form, but Food 4 Less carries Florida’s Natural brand in a 52-ounce waxed paper carton. (Walmart stopped carrying this in 2020).  Mayonnaise, olive oil, sesame oil: I am able to find these in glass bottles or jars. I have to go to Natural Grocers to buy organic mayo, though, as I can no longer find any mayo in glass jars at regular grocery stores. The Ojai Cook brand is good and the least pricey of the options, though it is still over $4 for a 16-oz jar. Thankfully, I don’t need much. For many recipes, I can substitute some or all of the mayo with fat free sour cream or Greek yogurt. Though these are only available in plastic…

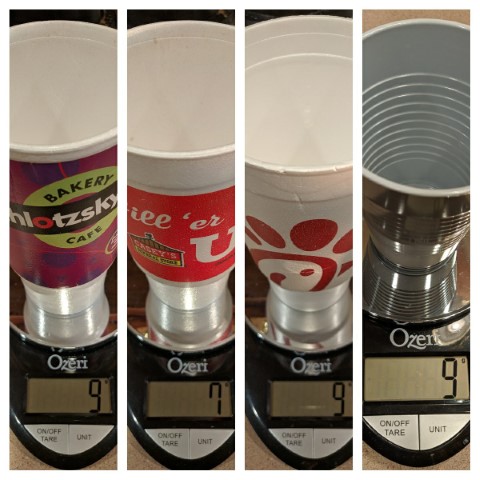

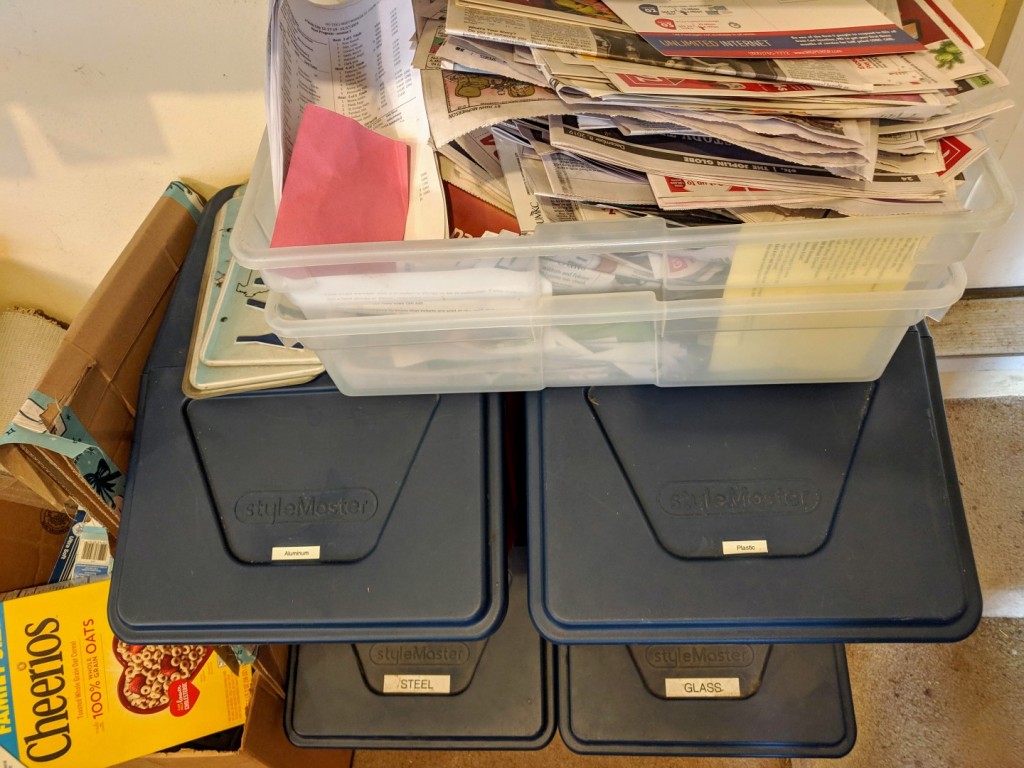

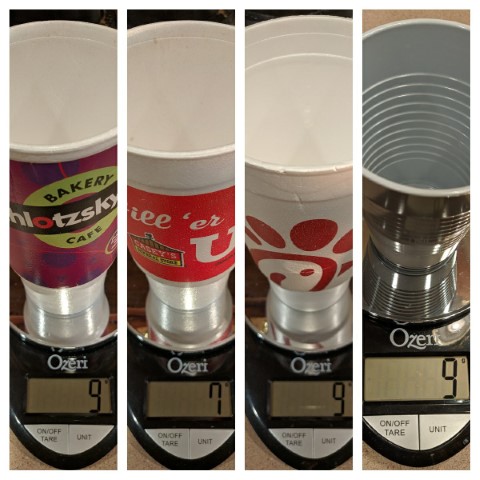

Mayonnaise, olive oil, sesame oil: I am able to find these in glass bottles or jars. I have to go to Natural Grocers to buy organic mayo, though, as I can no longer find any mayo in glass jars at regular grocery stores. The Ojai Cook brand is good and the least pricey of the options, though it is still over $4 for a 16-oz jar. Thankfully, I don’t need much. For many recipes, I can substitute some or all of the mayo with fat free sour cream or Greek yogurt. Though these are only available in plastic… Beverages: While I was committed to no disposable plastic, the rest of my family was not. My daughters continued to purchase smoothies in Styrofoam, iced coffees, Gatorade in plastic bottles, and protein shakes in unrecyclable multilayer packaging. On the other hand, they use refillable water bottles often and I don’t think we purchased any bottled water at all this year. We also now have some powdered Gatorade that one daughter chose to buy (on her own) rather than buy a case of it in plastic bottles. My example is rubbing off some.

Beverages: While I was committed to no disposable plastic, the rest of my family was not. My daughters continued to purchase smoothies in Styrofoam, iced coffees, Gatorade in plastic bottles, and protein shakes in unrecyclable multilayer packaging. On the other hand, they use refillable water bottles often and I don’t think we purchased any bottled water at all this year. We also now have some powdered Gatorade that one daughter chose to buy (on her own) rather than buy a case of it in plastic bottles. My example is rubbing off some. Other refrigerated or pantry items:

Other refrigerated or pantry items: